What Is Constitutional Growth Delay? A Complete Parent Guide

Understanding the “Late Bloomer” Pattern in Kids— What Is Constitutional Growth Delay (CGD)?

Constitutional Growth Delay (CGD)—also known as constitutional delay of growth and puberty—is one of the most common reasons children are shorter than their peers. It is a benign, non-disease growth pattern in which a child grows normally, just on a later timeline than average.

Most importantly: children with CGD almost always reach a normal adult height.

This guide explains what CGD is, why it happens, how doctors diagnose it, and when parents should consider a pediatric endocrinology evaluation.

Key Takeaway (What Parents Want to Know First)

Children with Constitutional Growth Delay typically:

-

were normal size at birth

-

slow down in height around ages 2–4

-

grow steadily but stay short compared with peers

-

enter puberty later than classmates

-

experience a delayed—but strong—pubertal growth spurt

-

reach a normal or near-normal adult height

What Exactly Is Constitutional Growth Delay?

Constitutional Growth Delay is a normal variant of growth—not a disease or endocrine disorder.

Children with CGD follow a healthy growth pattern, but their biological clock runs slower.

The delay affects:

-

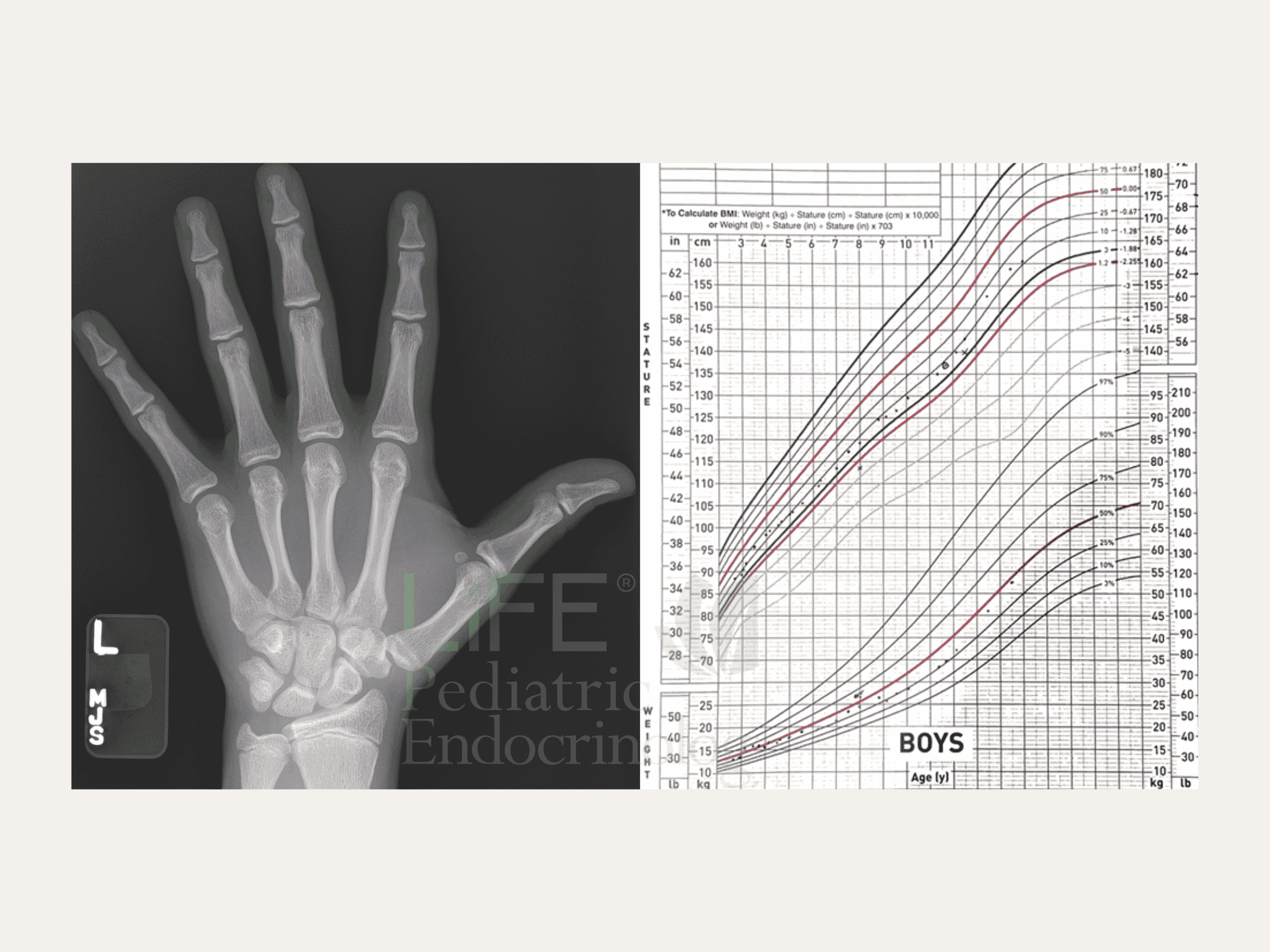

Bone age (delayed vs. actual age)

-

Puberty timing

-

Growth spurt timing

Because their bones are younger, these children still have more time left to grow, even when peers have finished. You can read more about what a bone age is here.

What Causes Constitutional Growth Delay?

CGD is strongly linked to genetics and family patterns.

At least one parent often reports:

-

“I was the shortest kid in my class.”

-

“I didn’t hit puberty until high school.”

-

“I grew after senior year.”

This inherited timing difference affects how quickly the growth plates mature but does not indicate disease.

There is no evidence that nutrition, hormones, illness, or environmental exposures cause constitutional delay.

Signs & Symptoms of Constitutional Growth Delay

Parents often notice:

1. Shorter height compared to peers

Typically below the 3rd–10th percentile, while weight may be normal.

2. Normal growth velocity

Children grow consistently each year, just at a steady pace.

3. Delayed puberty

Boys may not show testicular growth until 13–14.

Girls may not begin breast development until 12–13.

4. “Young-looking” appearance

Kids may look younger than their classmates due to delayed bone maturation.

5. Family history of late bloomers

This is one of the strongest clues.

How Pediatric Endocrinologists Diagnose Constitutional Growth Delay

Diagnosis must be made carefully, because CGD looks similar to several medical disorders early on.

Evaluation typically includes:

1. Bone Age X-Ray (Most Important Test)

A simple X-ray of the left hand/wrist tells us the biological age of a child’s growth plates.

-

Bone age younger than actual age → consistent with CGD

-

Bone age equal to actual age → consider other diagnoses

A delayed bone age means more growth potential remains, which is why CGD children often “catch up” later. You can learn more about when growth plates close here.

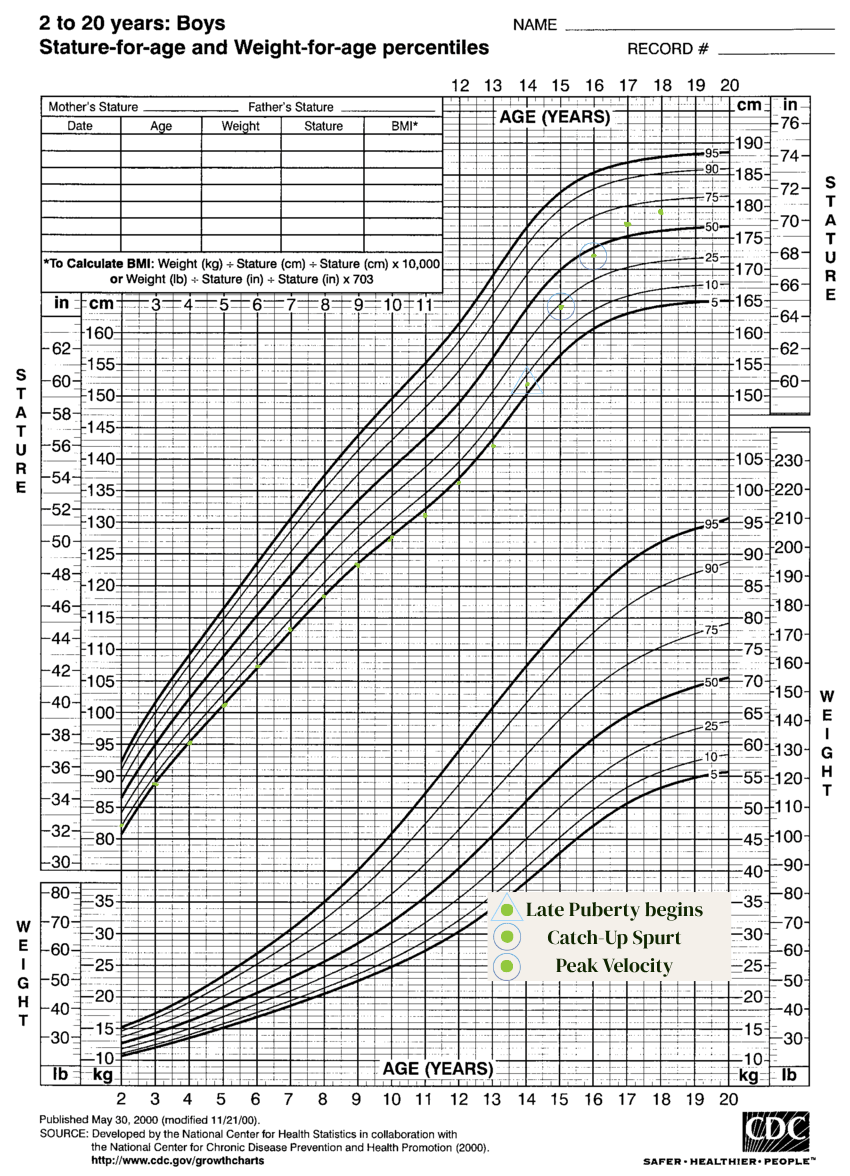

2. Growth Charts & Growth Velocity

Doctors look at how quickly a child grows yearly.

In CGD, velocity is normal (5–6 cm/year before puberty).

3. Labs (If Needed)

To rule out other causes of short stature, physicians may check:

-

Thyroid levels

-

Growth hormone pathways (IGF-1)

-

Celiac screening

-

Inflammatory markers

Most children with CGD have relatively normal labs.

How Constitutional Growth Delay Differs From Growth Hormone Deficiency

| Feature | CGD | Growth Hormone Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Age | Delayed | Delayed or normal |

| Puberty | Delayed | Often delayed |

| Growth Velocity | Normal | Low |

| Labs | Normal | Abnormal GH/IGF-1 |

| Final Height | Normal | Often short without treatment |

Because both conditions can appear similar, evaluation by a pediatric endocrinologist is essential.

Will My Child Catch Up? Understanding the Growth Timeline

Yes — almost all children with CGD achieve normal adult height.

Typical CGD timeline:

-

Ages 2–4: growth slows

-

Ages 4–12: steady but below peers

-

Ages 12–15: delayed puberty

-

Ages 14–17: late but strong growth spurt

-

Ages 16–20: continued catch-up growth

Many patients grow significantly after classmates stop.

When Should Parents Seek a Pediatric Endocrinology Evaluation?

Seek an evaluation if your child:

-

is significantly shorter than peers

-

shows no signs of puberty by age 13 (girls) or 14 (boys)

-

has a concerning growth velocity (<4 cm/year before puberty)

-

has chronic medical symptoms

-

has a normal bone age but remains very short

-

you simply need clarity, reassurance, and a professional growth plan

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is Constitutional Growth Delay a disease?

No. It is a normal growth variant, not a medical disorder.

Does my child need medication?

Rarely. Most children grow normally on their own.

Can growth hormone help?

Only if your child has another condition. CGD alone does not require GH therapy.

Will my child be short forever?

Almost always no. Kids with CGD have extra years of growth due to delayed bone maturation.

When will puberty start?

Typically 1–2 years later than average—but still normal.

Ready to Understand Your Child's Growth?

If you’re worried about your child’s height or puberty timing, a growth evaluation can provide clarity and a precise plan.

Schedule a Growth & Puberty Consultation with Life Pediatric Endocrinology—the nation’s leader in integrative, evidence-based pediatric endocrinology.

Our specialists analyze bone age, growth velocity, hormones, nutrition, and genetics to give your family answers and confidence.

About the Author

Dr. Kelli Davis, DO is a board-certified pediatric endocrinologist at Life Pediatric Endocrinology. Trained at Vanderbilt University, she specializes in growth, puberty, and bone health. Dr. Davis is passionate about helping families understand their child’s growth journey and make informed decisions with clarity and confidence.

References

-

Allen DB, Cuttler L. Short Stature in Childhood — Challenges and Choices. NEJM 2013; 368(13):1220–8.

-

Raivio T, Miettinen PJ. Constitutional Delay of Puberty Versus Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 33(3):101316.

-

Barroso PS et al. Clinical and Genetic Characterization of a CDGP Cohort. Neuroendocrinology 2020; 110(11–12):959–966.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

When to Worry About Your Child’s Growth: Early Puberty & Late Bloomers

When Do Growth Plates Close?